I am younger than I am now and wearing a green velvet dress. My face is painted and I have violet flowers tucked within my dark hair. My earrings drip to my shoulders and I feel dazzlingly happy as I sit in the passenger’s seat beside the man I love (and who loves me!) in his fast car–we are going to a faraway party in Western Pennsylvania. It is winter and still bright outside, the windows are sealed, but as we leave his house and round through the winding roads leading to the highway, a blue silence like a haze descends over us. His fingers grip the steering wheel, his knuckles whiten, and his mouth becomes menacing.

“I can’t believe you,” he hisses, still staring at the road ahead.

“What? What?” I ask, bewildered. I have no idea what I have done wrong.

“Think,” he spits, letting his tongue slap the roof of his cold mouth, “You like to do that, don’t you?”

I search the interior of the car for clues. Door handle. Dashboard. Radio nozzles. My slinky purse on the floorboard.

“What?” I beg.

His face is tight like a canvas tent pinned to breakable earth. I stare at his profile and after a punishable time, he snarls, “Your chin. It’s disgusting. You disgust me sometimes.”

I instantly free my hand of my glove and brush the sides of my face and feel the distinctive bristles, a family heirloom–my mother and her mother were flowery too. I want to shrug. I had felt resplendent.

“People will laugh at you. Everyone can see,” he scolds me.

“I don’t think it matters,” I say weakly, but he continues to humiliate me and to augur an inevitable humiliation by others until I am crying and he turns the car around. “If you loved me, you’d take care of that.”

I see my tears transforming into sea ice as they drip downward and this slender ice grass grows high and sharp in the car like an ice meadow. My knees shake as the glacier glass ascends around us with polar majesty–can’t he see? Blue ice stalks grow over the armrest and between our legs, from the vents, on the dash, while the polar chill strangles all the flora and fauna of my being, and everything is winter suddenly. When we reach his house, I assume we are finished for the evening–or forever–but instead he shuts off the engine, and says quietly, “I’ll wait here. There is a razor in my cup.”

As I open the car door, I imagine the ice stalks following me, becoming water, and flooding out of the car, but as I turn back around, the ice has not melted but grown thicker and now the man is encased in the ice, unrecognizable as a blur. I slowly let myself back into his house and climb up to the bathroom, where I stare at myself in the mirror. Am I a barbarian? My makeup is ruined, two smudgy charcoal trails that fall over my cheeks, my hair is fussed and raging from our argument. I pick up the razor and lean over the sink, still tearful as I shave off the undesirable thistles of me. As I do it, I wonder what I am doing. Then, like a clear burst of air, a bird of thought, Athena’s owl, Frida Kahlo’s spirit flies into the room. That unmistakable whiff of moustache, the monobrow, but mostly, her defiant eyes. I go to the party, shaven. I drink and dance, but in my heart, I feel the drought coming, the cracking of something once fertile, but it isn’t my dermis – it is something else.

Frida Kahlo, Julien Levy, American; From the collection of: Philadelphia Museum of Art

How and why do so many folks find inspiration in Frida Kahlo, and not just in her paintings, but in how she lived her life? “For [American Art Historian] Parker Lesley, she epitomized ‘the Byzantine opulence of the Empress Theodora, a combination of barbarism and elegance” (Phillips 95). Is it this — her timeless brutal regality without mystification? And is it part thrill of her unorthodox face, more familiar and universal than the faces on most world currencies? With her radical choices, she gives us permission to be ourselves. Carlos Phillips Olmedo, Director General of Museums Dolores Olmedo, Frida Kahlo y Diego Rivera Anahuacalli, claims “There is art that is so highly personal in nature that it becomes universal. This is true of the art of Frida Kahlo” (Henestrosa & Wilcox 10). London’s Victoria and Albert museum’s current exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, seeks to answer this question and more. And it succeeds, without falling into idolatry, hagiography, or beatification. Or an uninventive mise-en-scène of a mad misunderstood genius. Or myth-making.

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up is an exhumation of a subversive feminist-artist-activist who is still able to teach us new ways to live and think. By unearthing Kahlo’s personal artifacts (literally, the artifacts presented were revealed in 2004 from Kahlo’s sealed bathroom), we do not supersede her paintings. Instead, swimming through the blue exhibit rooms (painted blue in homage to her Casa Azul home in Coyoacán, Mexico), visitors temporarily evolve the lateral organs of fish and are able to feel all the vibrations, impulses, histories, and pressure gradients in Kahlo’s life, which imbued her easels and her untraditional canvases (her own plaster corsets and prosthetic leg) with her singular force.

The exhibition’s co-curator Circe Henestrosa writes, “It is her construction of her identity through her ethnicity, her disability, her political beliefs and her art that makes her such a compelling and relevant icon today” (14). Henestrosa’s words echo Olmedo’s idea that it is the highly personal aspect of Kahlo that draws in her acolytes; Kahlo exemplifies how mess and integrity in your art and lifestyle is attractive, whereas being too broad and noncommittal in order to please does not actually appeal in the long-term. The exhibition, which also throws light on modern Mexican history, reminds us that this daughter of a German immigrant and a Mexican woman “wore many hats” as people say today–she even reinvented her own birthday, turning her clock forward by three years, so she could be a daughter of the 1910 Mexican Revolution.

Frida Kahlo’s wardrobe inspired by the the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Photograph Javier Hinojosa

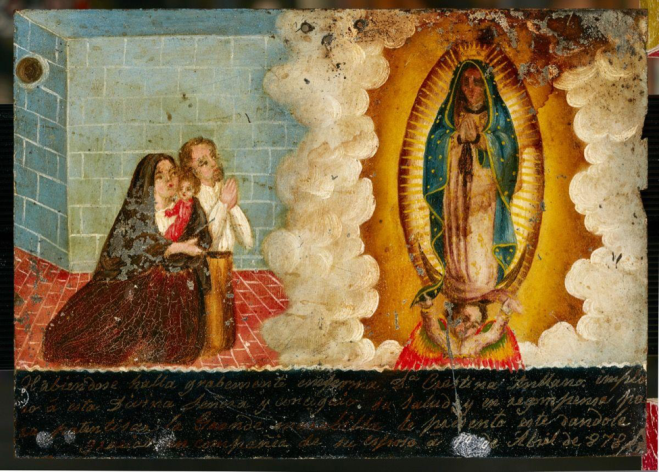

Some reviews of this exhibition bemoan a lack of Kahlo’s paintings or suggest we are ogling Kahlo with a modern gaze. Jonathan Jones of The Guardian writes, “This exhibition reinvents Kahlo as a 21st-century artist whose life was a kind of performance…” and “I suppose this is what artistic fame looks like in 2018.” I would counter that all lives are performances and in the most enlightened scenario, the performance is a person living out their essences for their own fulfillment and pleasure, which Kahlo demonstrates. There is a difference between performance and self-publicity; I wager that Kahlo was less interested in self-publicity than contemporary artists and social media darlings are today, but she might have been just as much a performer. For example, while viewing her painting Self Portrait Along the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States at the exhibit, the curators remind us that Kahlo stated, “The most important thing for everyone in Gringolandia [America] is to have ambition and become ‘somebody,’ and frankly, I don’t have the least ambition to become anybody.” Kahlo didn’t want to become somebody, which is what the performer does. Kahlo was comfortable with the existing contradictions of her life, body and history; a publicity campaign-minded person also prefers a more linear and uncomplicated message. For instance, the exhibition takes us into Kahlo’s home where she spent most of her life, a place just outside of Mexico City. She and her partner Diego Rivera collaged her home’s interior walls with tiny votive (or retablo or ex voto or lámina) paintings (she collected more than 400), because they were part of Kahlo’s national and maternal history, not because she actually believed in god and the saints (Gotthardt). The votive influence is also felt in her own art and the V&A exhibition features many such votives to consider along with their context within Mexican history.

Votive by unknown painter (Mexican, 19th century). Image courtesy of El Paso Museum of Art

Other reviewers wish there had been a more unequivocal focus on her communist politics, or her atheism or feminism. I will note The Communist Manifesto was being sold alongside dozens of Kahlo biographies at the robust gift shop, and a black-and-white video of Kahlo, Leon Trotsky, and Diego Rivera at Casa Azul plays early in the exhibition. In addition, an exhibit highlight was Kahlo’s plaster orthopedic corsets, one of which featured the unmistakable symbol of proletarian solidarity, the red hammer and sickle. Seemingly, co-curators Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa chose to “show” Kahlo’s story instead of “tell” it, which means the likes of Chekhov and legions of creative writing teachers would enjoy the storymaking of this exhibition.

Ultimately, underlining this empowering and uplifting exhibition is a tension between the Flaubertian notion that the artwork is all that should matter, and the alternative, that the artist’s life is worthy of study, and enhances our experience with their art or with our world. Furthermore, there is a subtler idea, that artists themselves are deserving of our time, but only if we are engaging in discourse concerning “serious” matters, like the artist’s politics or gender-bending. If we are entranced by Kahlo’s stained lipstick print on a photo of Rivera or the grey-green stone beads she most likely acquired from Maya sites in southeastern Mexico, we are somehow superficial, plebeian, mere idolaters. All these ideas are myopic and do not apply to this exhibition. One easy reason is that humans, particularly women, are still enduring in binaries, boxed like madonna or jezebel as caring wife or career woman, or problematic sub-boxes like muse, manic pixie dream girl, feminazi. Kahlo provides us with a modular life; she does not live in a box–she lives in sieves. Things pass through her and she passes through them, from Tehuana headdresses to medical operations to being Madame Rivera to engaging in her infidelidades to being a person with lifelong physical disabilities. All these passages infuse her artwork and give us a new way to consider being human or woman or artist or bodied or partner or citizen.

In the United Arab Emirates today, because of her physical limitations, Kahlo would be considered a Person of Determination, which is a new and bold take on inclusive language issued by Dubai’s ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al-Maktoum. This distinction, decreed in time for March 2019’s Special Olympics World Summer Games in Abu Dhabi, is a far cry from the language many folks grew up using around disability– and language changes thinking. ‘People of Determination’ signs are now found everywhere in the UAE, from airports to queues at the Louvre Abu Dhabi. And if there is any doubt in the language, look to Kahlo for affirmation. The exhibition reminds us that Kahlo once said, “I am not sick. I am broken. But I am happy as long as I can paint” and Tristram Hunt, Director of the V&A, states, “Her rejection of gender orthodoxy and conventional fashion–as an artist who also transcended disability–allowed her to forge a unique identity which spans ages, gender and geography in its global appeal” (Henestrosa & Wilcox 11). In fact, the opening text within the exhibit is organized under the titles ‘Roots’ and ‘Sickness’ because these two elements of her life are the muses of so much of her artwork. It is gratifying to understand the multifarious influences in her life and not perpetuate the idea of the artist being visited by some mythical muse who imparts ideas in the artist’s hands like the spirit visiting the Four Evangelists. There is hard reflective work and corporal pain inherent in every painting, evidenced in works such as The Broken Column. Furthermore, through ‘Roots’, we learn of her photographer father, who liked to take self-portraits, perhaps animating her own lifelong obsession with self-portraiture.

John Madejski Garden, Samantha Neugebauer

John Madejski Garden, Samantha Neugebauer

On the afternoon I visited the exhibit, the crowd was surfeit with matriarchal magnetism—mothers, daughters, grandmothers, sisters, girlfriends, all huddling over captions, smiling, reading, and nodding their heads together. It was especially arresting to see young boys enchanted by Kahlo, grasping their mother’s hands and asking questions about her life, ideas, and art. There was innocence and hope inherent in these little boys’ fascination; they had not yet been conditioned to fear powerful women, to feel intimidated, or to fight (sometimes subconscious, sometimes conscious) urges to want their women conformed into boxes. Outside, in the museum’s John Madejski Garden, children leaped inside a steel face of Kahlo for photos of the flower queen. It felt like a safe haven in a world that is as of late (as of always) hostile towards women. Kind of like how, according to curator Adrian Locke, Kahlo’s Mexico felt to many artists, photographers, and academics during the outbreak of WWII and rise of fascism in Europe. At this time “Mexico was viewed as a safe haven that welcomed refugees” (Henestrosa & Wilcox 46). Kahlo, likewise, has become a stiff caryatid holding up new ideas for us to consider, but also someone we can stand below for pride and safety.

Back inside the museum, there was genuine excitement in the air; it was a different energy than the V&A’s relatable David Bowie Is exhibition or even another exhibit of a female art icon, Georgia O’Keeffe, which was on at the Brooklyn Museum in 2016. Both these exhibitions were extremely well-done and expansive, but in some ways, Kahlo’s subversion is more necessary now, more timely. Kahlo did not live to see many of the dark repercussions of communist leadership, so, we cannot predict exactly what her politics would look like today; however, we can look to her art and lifestyle for elements of her politics which would still serve us well, especially if we feel trapped in the grid of capitalism but aren’t sure what to do. For example, many of the costumes on display were handmade or altered by Kahlo herself. Her wardrobe was intentional, inclusive, and I’ll say, the wardrobe of an environmentalist. Her clothing was typically comprised of a huipil (square-cut tunic) and an enagua (skirt) with an holán (flounce). She wore the same accessories and clothing frequently, as evidenced in many photos and paintings reunited in this exhibit with Kahlo’s real wardrobe. She also kept clothing that was imperfect —paint splatters, ink, cigarette burns, and other marks of life. She altered, shared, and borrowed stones, beads, fabrics; some of her famous swaps were from notables like her comrade Picasso and Peggy Guggenheim (Phillips 89). She was generous and inventive. Alternatively, in a recent article about Rent the Runway in the The New Yorker, Alexandra Schwartz writes, “…the average American buys sixty-eight items of clothing, eighty percent of which are seldom worn; twenty percent of what the $2.4-trillion global fashion industry generates is thrown away” (46). If we admire Kahlo’s style, why not create our own and eschew the anodyne of fast fashion? We don’t need to imitate her look, but rather follow her attitude towards style cultivation and wardrobe accumulation.

Other unmissable exhibition highlights included a short clip of Miguel Covarrubias’ film El Sur de México, which features strong female figures from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, an inspiration of Kahlo’s as reflected in her artwork and her élan. The famed Mexican writer Andrés Henestrosa from Oaxaca was a friend of Kahlo’s and Henestrosa gave Kahlo her first Tehuana dresses (Phillips). Furthermore, Covarrubias had stated, “To the average city Mexican, a Tehuana is as romantic and attractive a subject as a South Sea maiden to an adolescent American” (Phillips). Once you familiarize yourself with Tehuana sartorial traditions and post-revolutionary nationalism, it is impossible not to discern its spell on Kahlo.

A key item for poetry lovers is Kahlo’s copy of Leaves of Grass (the Spanish translation of Whitman’s poems by Armando A. Vasseur was found at Kahlo’s deathbed). Lastly, make sure to check out the exquisite bracelet from China that Kahlo wore; it is featured in the exhibition’s last room.

Victoria and Albert Museum Gift Shop, Samantha Neugebauer

Following the exhibit, one exits, rather obviously, through the gift shop. While the capitalistic cacophony of Kahlo goods for sale might have elicited disdain from the artist if she were around to witness it, there is a sense that the eager shoppers have a specious impulse that by buying a flowery headband or bulbous necklace, they will never detox from the euphoria of their Kahlo experience and the empowerment she radiates. These actions come from a good place; they also support the museum (which has free admission)–and in some cases, contemporary Mexican artisans. There is not only a gift shop of Kahlo wares as your exit, but also Kahlo-inspired souvenirs and books in the V&A’s main gift shop. In this space, you’ll find exclusive pieces of jewelry and other fashion goods, like painted guaje purses, by female Mexican artists, such as Iris De La Torre of Guadalajara, Carla Fernández of Mexico City, and Franco-Mexican designer Sophie Simone Cortina, who all designed pieces especially for this exhibition. One necklace by Cortina called ‘Hummingbirds’ expresses how these birds represent good luck in Mexican culture and the piece also evokes the term of endearment Rivera used to refer to Kahlo’s eyebrows: her hummingbirds. I purchased a pair of chaquira earrings by Carla Fernández, made in collaboration with the Mooy artisans from the San Pablito community, which feature one figure wearing a long skirt and another in trousers. When I asked for this pair from the salesperson, a young seemingly kind-hearted guy asked, “Oh, you want the boy and girl pair or the two girls?” There was another pair by Fernández with both figures in skirts. I was temporarily taken aback that we were still making distinctions on sex related to a human’s clothing choices, especially in such close vicinity to the masterful Kahlo exhibition, one that even featured photographs of Kahlo in trousers. That brief experience was quickly usurped by my eavesdropping as I heard a young Glaswegian-accented boy make pleas to his father to buy some bright plastic bracelets as he slipped several of them up his thin arms. His father quickly instructed him to “Put those back…those are for girls”.

Nevertheless, these two antidotes did not break the magic of Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up. In truth, these final brief episodes bolstered my reverence for the exhibition, its necessariness, and seriousness. Ultimately, it makes me believe, as I finish writing this while brushing the small dark hairs on my chinny chin chin, that we have as much to learn from Kahlo about how she lived her life, in her body, with her uncompromising body hair, and in her clothing, as we do from her paintings themselves.

Victoria and Albert Museum Gift Shop, Carla Fernández

References

Frida Kahlo Making Her Self Up. 16 June 2018- November 2018, Victoria and Albert Museum,

London.

Gotthardt , Alexxa. “A Brief History of the Mexican Votive Paintings That Inspired Frida

Kahlo.” Artsy, 1 Nov. 2016,

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-traditional-mexican-votive-paintings-that-inspired-frida-kahlo.

Henestrosa, Circe, and Wilcox, Claire, editors. Frida Kahlo Making Her Self Up. London, V&A Publishing, 2018.

Phillips, Claire. “Frida Kahlo’s Jewellery.” Frida Kahlo Making Her Self Up, edited by Circe

Henestrosa and Claire Wilcox, V&A Publishing, 2018, pp 85-97.

Schwartz, Alexandra. “Costume Change.” The New Yorker. 22 October 2018: 44-49.

Artwork by Frida Kahlo, “The Two Fridas”, 1939.

Not much to write about myself at all.

LikeLike

Hello from columnspinfile-address_data.dat-1. I’m glad to be here. My first name is spinfile-names.dat.

LikeLike

I’m learning spinfile-languages.dat literature at a local university and I’m just about to graduate.

LikeLike

I have two brothers. I love spinfile2-hobbies.dat, watching TV (spinfile-tvseries.dat) and spinfile2-hobbies.dat.

LikeLike